Decommissioning a Nuclear Power Plant

The United States last nuclear reactor began construction in 1973 and then opened up in 1996. As of this blog post, the United States has not built a new plant since then. So why did we stop building plants?

Besides the obvious regulations and strict requirements, the estimated price to build a plant was vastly incorrect way back when these plants were being constructed. The 1960s/1970s raced to build more reactors for the assumed growth in electricity demand. Plenty of plants were canceled during planning or construction, or prematurely shut down due to funding.

As of this blog post, we currently have 99 commercial reactors in the United States, most of which were built three decades ago. So can these reactors last forever? For most of these reactors they have a 40 year license from NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission), which can be renewed in 20 year increments. These strict license force a facility to go through an expensive decommission process if they chose to shutdown.

We can take a look at the current sites in the states via this link. From this list, we can pick a random reactor. In this case, the Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Unit 4 in Homestead, Florida.

Location: Homestead, FL (25 miles S of Miami, FL) in Region II

Operator: Florida Power & Light Co.

Operating License: Issued - 04/10/1973

Renewed License: Issued - 06/06/2002

License Expires: 04/10/2033

Docket Number: 05000251

Reactor Type: Pressurized Water Reactor

Licensed MWt: 2,644

Reactor Vendor/Type: Westinghouse Three-Loop

Containment Type: Dry, Ambient Pressure

We can see the site was renewed and is set until 2033. So lets pretend this site does not renew, how does a nuclear plant shut down? The first thing needed is money and secondary payment companies in case the licensee fails to pay.

The NRC estimates costs for decommissioning a nuclear power plant range from $280-$612 million.

There are 3 main types of decommissioning strategies, which are listed below.

-

DECON - This is an immediate dismantling of the facility where radioactive elements are either removed or decontaminated. This is an expensive option as the price to decontaminate highly radioactive elements can be costly.

-

SAFSTOR - This is a deferred dismantling where the facility is partially shutdown and simply monitored for nearly 60 years. After this long time, the radioactivity has decayed and the less expensive dismantling can occur.

-

ENTOMB - This is where all radioactive elements of the facility are permanently encased until decay is complete. As no NRC-licensed facility has chosen this option, we don't know much about it.

Most facilities tend to use a combination of DECON and SAFSTOR, in which some material except the spent fuel is removed. So the facility is just an interim storage of spent fuel, which requires a less restrictive license.

This tiny image from the NRC can visually explain the above three options.

https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/decommissioning.html#phases

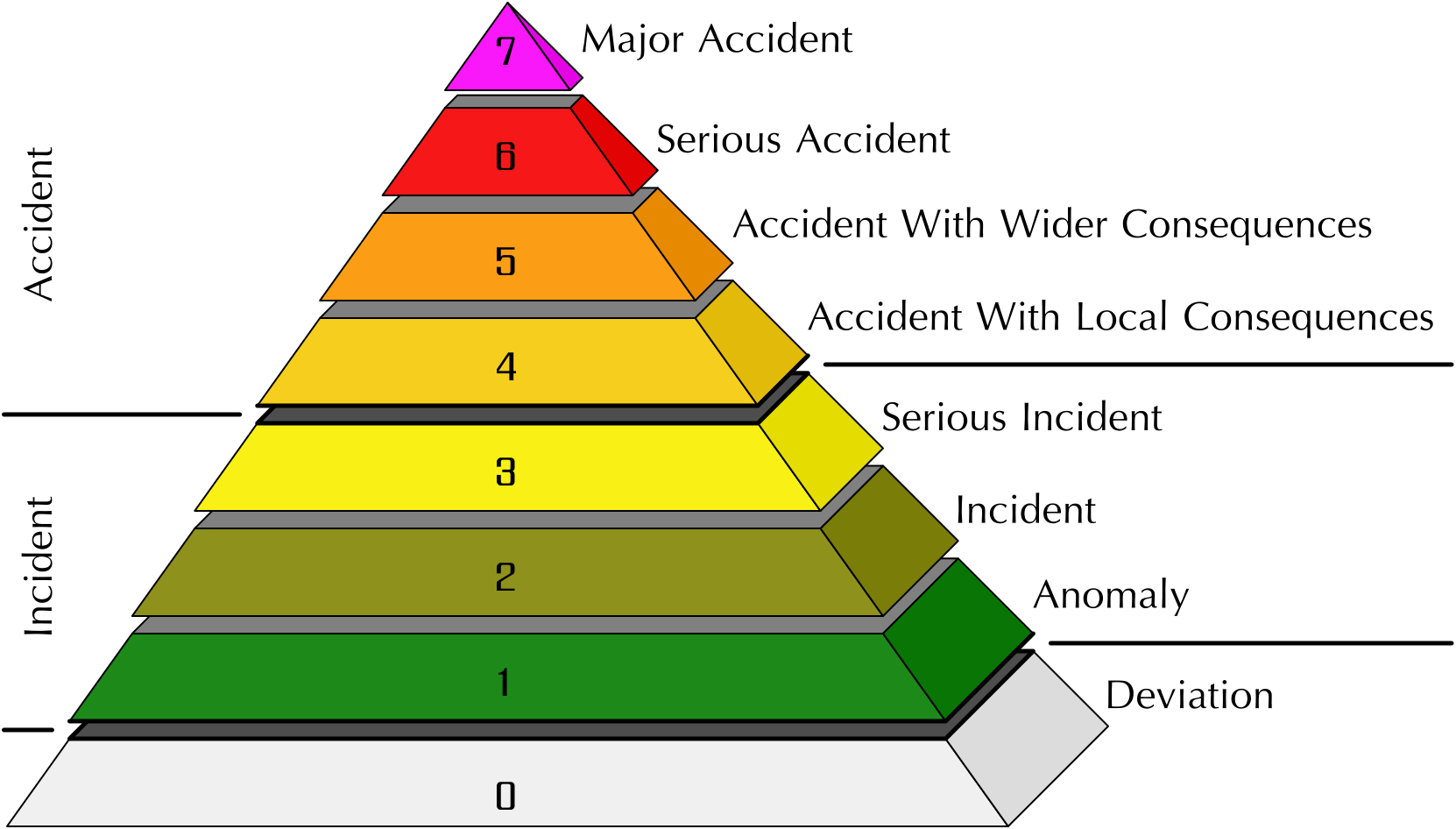

Switching gears, lets talk about accidents in the industry. After the terrible events in Fukushima, regulation in other facilities across the world increased. This once again stalled the public perception of additional nuclear facilities. When discussing this incidents, the entire world agrees on the same scale when classifying nuclear events.

By Silver Spoon - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

The only two events to be labeled as Level 7 were

These events showed what can happen when mistakes are amplified in the field of nuclear energy. With every accident, other sites learn from it. We can see the NRC has many documents directly related to the outcome at Fukushima.

US Plant Inspections following Japan Event

Plant-Specific Actions in Response to the Japan Nuclear Accident at Fukushima Dai-ichi

Nuclear facilities will always have my interest due to the complexity, regulations and pure power all these facilities have. I think my next post will take a look into the Lake Chagan as the story involving it is quite interesting.

Featured photo by Frédéric Paulussen / Unsplash